Recent events have uncovered vulnerabilities in versions of SSL/TLS - protocols that many developers and engineers have historically taken for granted as reasonably secure unless certificates are leaked or encryption techniques become outdated. As these security flaws are made public, developers often discover ancillary issues as patches are installed, old protocols are invalidated, and new ones become mainstream. POODLE is a great example of this. It is standard practice for older protocols to be supported for a period of time and then disabled when new certs are issued. If engineers haven't scrutinized the current state of their machines and the applications that run on them, they could be in for a rude awakening.

The Problem

Our teams are trending more toward transient - rather than fixed - environments to test on. Consequently, we're working with devops to ensure that we can take advantage of virtualization and automated provisioning. There are many upsides to push-button environments, many of which I will not get into with this blog post. However, the primary one I'm concerned with at the moment is the fact that a machine that is base-provisioned successfully comes up in a known, repeatable state. While we aren't where we need to be yet with this goal, we are spinning up new virtual machines using this approach far more often than in the past and it uncovers the one-off, undocumented configuration adjustments that are often done on the fly on bare-metal servers to resolve problems.

One such newly provisioned virtual machine hosts an application that, among other things, is responsible for communicating with a downstream API hosted by one of our vendors. The specific piece of functionality in question isn't often tested - it is usually mocked in order to isolate our code from dependencies - but a recent enhancement I was working on required a full integration test in order for us to feel comfortable releasing to production.

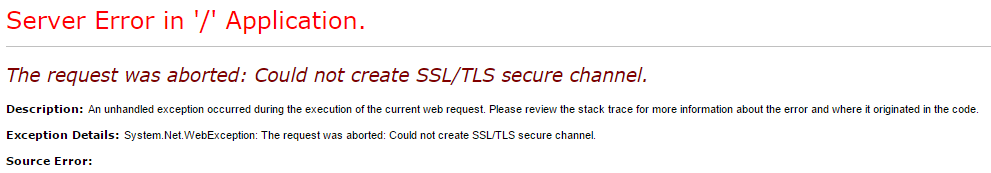

Everything was going smoothly until the application made the web request to the third-party API. Thanks to the IIS configuration settings in our development regions, I was able to view the type of error no one wants to see on their screen:

Ouch. There are clearly several problems here. The first is that the HttpClient issuing the web request doesn't set an appropriate callback function for handling certificate errors when establishing the SSL handshake - something easily remedied in code. The second is that the secure connection couldn't be established at all. This is where the majority of my investigation began. One of the problems with this type of error is that even with the message and stack trace it can sometimes be difficult to pin down the root cause unless there's a problem with the cert itself.

The Investigation pt. I - The Certs

The first thing most developers will do when encountering an SSL/TLS error is to check out the certificate. This is the easiest thing to verify and bad certs are the root of the problem more often than not. Navigating to the API's URL in Chrome revealed that the cert was indeed valid, issued by a trusted Certificate Authority, and encrypted using a modern approach - in this case, TLS 1.2.

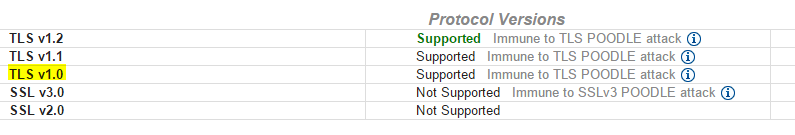

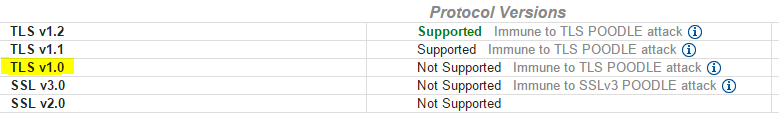

Out of curiosity, I built a test application that would make the same API call (an innocuous read) against our vendor's test and live APIs. The read against the test API failed once again. However, the read against the live API established the secure channel just fine and produced a predictable AuthN/AuthZ error from the API itself. Both certs were valid. Both issued from trusted CAs. But one worked with our application, and one did not. This was getting more interesting. There was clearly some x-factor here at play that I hadn't discovered yet. The first step toward discovering what it was involved learning as much of I could about the certificates themselves. Identifying any difference might pay dividends. Luckily, there are any number of tools available to perform a detailed inspection of a Cert file. My company offers an internal tool that we can use, but a bit of googling revealed SSL Analyzer by Comodo CA. Just enter a domain, and it'll reveal anything about the Certificate you need to know. There's a wealth of information available, but after looking things over there was one key difference that jumped out:

Good API Request

Bad API Request

The cert used by their test API doesn't support TLSv1.0, but the production cert does. This is a common way for businesses force API clients to make appropriate adjustments by breaking Test or Beta environments beforehand. Things were starting to become clearer. The next step was to analyze the state of the development VM in question.

The Investigation pt. II - The Server

Quick internet searches for Windows Server and TLS 1.2 produced a number of results, mainly blog posts for enabling TLS 1.2 in Windows Server 2008 and 2008 R2, which supports it but ships with TLS 1.2 in an "off" state. The machine in question is Windows Server 2012, which according to the MSDN supports TLS 1.2 without any changes to the registry required. Something didn't make sense. If it wasn't the server configuration, it had to be the application itself.

The Investigation pt. III - The App

The codebase is written in .NET 4.5. Investigation of the MSDN documentation and the Security Protocol Enumeration revealed the following:

namespace System.Net

{

[System.Flags]

public enum SecurityProtocolType

{

Ssl3 = 48,

Tls = 192,

Tls11 = 768,

Tls12 = 3072,

}

}

So clearly there is some support for TLS 1.1 and 1.2 built in to .NET 4.5. The library that enables an application to view and set supported protocols is already included in the .NET runtime.

namespace TLS

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

ServicePointManager.SecurityProtocol = SecurityProtocolType.Ssl3 | SecurityProtocolType.Tls | SecurityProtocolType.Tls12;

var supported = ServicePointManager.SecurityProtocol;

Debug.WriteLine("======================");

Debug.WriteLine("Supported Protocols: " + supported);

Debug.WriteLine("======================");

}

}

}

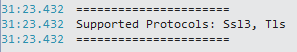

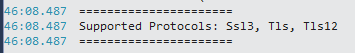

Running the above test program prints out the following:

Bingo. It turns out the default supported protocols are SSL3 and TLS! That same property has a setter as well. Enums support logical ORs to set multiple flags at once, so changing the test application to the following:

namespace TLS

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

ServicePointManager.SecurityProtocol = SecurityProtocolType.Ssl3 | SecurityProtocolType.Tls | SecurityProtocolType.Tls12;

var supported = ServicePointManager.SecurityProtocol;

Debug.WriteLine("======================");

Debug.WriteLine("Supported Protocols: " + supported);

Debug.WriteLine("======================");

}

}

}

The modified test program prints the following:

Adding the same line to the application's startup code resolved the issue. While I can see that it may be necessary to allow and disable certain Security protocols on an application-specific basis, it is both tedious and error-prone to force a developer to expressly add a more secure version that is natively supported by the server the machine is running on. So what tells the ServicePointManager to default to SSL3 and TLS 1.0? Can the default value be overridden in configuration?

Unfortunately, the MSDN article on the servicePointManager configuration element doesn't allow for such fine tuning. The encryptionPolicy attribute only allows for specifying whether encryption is required, not whether specific encryption protocols should be enforced. Going any further requires taking a dive into the code.

The Investigation pt. IV - The .NET Runtime - System.Net.ServicePointManager

I'm pretty happy you can now browse the .NET implementation without having to use a decompiler. It's as simple as heading over to http://referencesource.microsoft.com/.

Viewing the source reveals a few telling blocks of code:

The declaration of the variable here:

private static SecurityProtocolType s_SecurityProtocolType = SecurityProtocolType.Tls | SecurityProtocolType.Ssl3;

[RegistryPermission(SecurityAction.Assert, Read = strongCryptoKeyPath)]

private static void EnsureStrongCryptoSettingsInitialized() {

if (disableStrongCryptoInitialized) {

return;

}

lock (disableStrongCryptoLock) {

if (disableStrongCryptoInitialized) {

return;

}

bool disableStrongCryptoInternal = true;

try {

string strongCryptoKey = String.Format(CultureInfo.InvariantCulture, strongCryptoKeyVersionedPattern, Environment.Version.ToString(3));

// We read reflected keys on WOW64.

using (RegistryKey key = Registry.LocalMachine.OpenSubKey(strongCryptoKey)) {

try {

object schUseStrongCryptoKeyValue =

key.GetValue(strongCryptoValueName, null);

// Setting the value to 1 will enable the MSRC behavior.

// All other values are ignored.

if ((schUseStrongCryptoKeyValue != null)

&& (key.GetValueKind(strongCryptoValueName) == RegistryValueKind.DWord)) {

disableStrongCryptoInternal = ((int)schUseStrongCryptoKeyValue) != 1;

}

}

catch (UnauthorizedAccessException) { }

catch (IOException) { }

}

}

catch (SecurityException) { }

catch (ObjectDisposedException) { }

if (disableStrongCryptoInternal) {

// Revert the SecurityProtocol selection to the legacy combination.

s_SecurityProtocolType = SecurityProtocolType.Tls | SecurityProtocolType.Ssl3;

}

else {

s_SecurityProtocolType =

SecurityProtocolType.Tls12 | SecurityProtocolType.Tls11 | SecurityProtocolType.Tls;

// Attempt to read this from the AppSettings config section

string appSetting = ConfigurationManager.AppSettings[secureProtocolAppSetting];

SecurityProtocolType value;

try {

value = (SecurityProtocolType)Enum.Parse(typeof(SecurityProtocolType), appSetting);

ValidateSecurityProtocol(value);

s_SecurityProtocolType = value;

}

catch (ArgumentNullException) { }

catch (ArgumentException) { }

catch (NotSupportedException) { }

}

disableStrongCrypto = disableStrongCryptoInternal;

disableStrongCryptoInitialized = true;

}

}

That method gets called once in order to ensure that cryptographic protocols are set correctly. After looking through the entire class and working through the code, it appears as if it is driven by the presence of a registry value called SchUseStrongCrypto located in:

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\MICROSOFT\.NETFramework\{version}\SchUseStrongCrypto

NOTE: if you're working on cross-platform or mixed platform applications, you'll also want to set the same value in the WOW64 hierarchy, since a registry lookup will silently be routed there as well:

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Wow6432Node\MICROSOFT\.NETFramework\{version}\SchUseStrongCrypto

If that value is enabled (i.e. set to 1), the method will set the security protocols yet again. It then attempts to read a configuration value from AppSettings, of all places. Specifically, it appears as if it will do an Enum.Parse on the value of:

private static string secureProtocolAppSetting = "System.Net.ServicePointManager.SecurityProtocol";

/// ...

s_SecurityProtocolType =

SecurityProtocolType.Tls12 | SecurityProtocolType.Tls11 | SecurityProtocolType.Tls;

/// ...

string appSetting = ConfigurationManager.AppSettings[secureProtocolAppSetting];

try {

value = (SecurityProtocolType)Enum.Parse(typeof(SecurityProtocolType), appSetting);

ValidateSecurityProtocol(value);

s_SecurityProtocolType = value;

}

It turns out Enum.Parse will load the equivalent logical OR to my above example with a value of:

<add key="System.Net.ServicePointManager.SecurityProtocol" value="Ssl3, Tls, Tls12"/>

What if SchUseStrongCrypto is disabled? If that value disabled (i.e. set to 0), the disableStrongCryptoInternal flag will be set to true, and the following code block will execute:

if (disableStrongCryptoInternal) {

// Revert the SecurityProtocol selection to the legacy combination.

s_SecurityProtocolType = SecurityProtocolType.Tls | SecurityProtocolType.Ssl3;

}

Meaning, the system will once again use TLS 1.0 and SSL3 as 'secure' protocols. As we've seen with POODLE, SSLv3 is not in fact secure anymore. It seems like the best solution for now is to make things as explicit in code as possible.

Conclusions

All in all, I'm not too impressed. It looks like the only way to configure things correctly is to misuse a registry key and add in special application configuration. It'd be much more straightforward to add in a similar application configuration and use it in code. Furthermore, using the SchUseStrongCrypto correctly (i.e. enabled with a value of 1) could actually mislead a developer into thinking the enabled protocols are actually secure. Given the recent security vulnerabilities that have very quickly invalidated what were considered to be very secure protocols, I hope that Microsoft improves on this by keeping the flexibility to enable higher-level security in code, but also adds in the ability to holistically set a secure baseline of encryption protocols.